Every so often echoes of the Vedic past can be detected in the most obscure of items. Such is the case with the simple ‘piggy bank’. Was this staple of childhood nostalgia just a cute animal chosen at random or is there a deeper hidden meaning? If you promise not to squeal we’ll give you the clues.

The oldest known piggy banks have been discovered dating to the 13th Century from the Majapahit Empire of Indonesia. This Hindu-Buddhist Empire centered in Indonesia, stretched from Singapore, Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines. It acted as a major trading center with all of the surrounding lands including as far off as the Vijayanagara Empire of south India. Because of this commerce individuals needed a place to store their coins.

In the local Javanese language the word ‘celengan’ meant both ‘having the likeness of a wild boar’ as well as ‘savings’ or ‘wealth’. These celengans were crafted into the first piggy banks made of clay complete with an opening to deposit coins. The image of the boar, known for wallowing in the mud, was thus crafted as earthenware and was associated with wealth and good fortune.

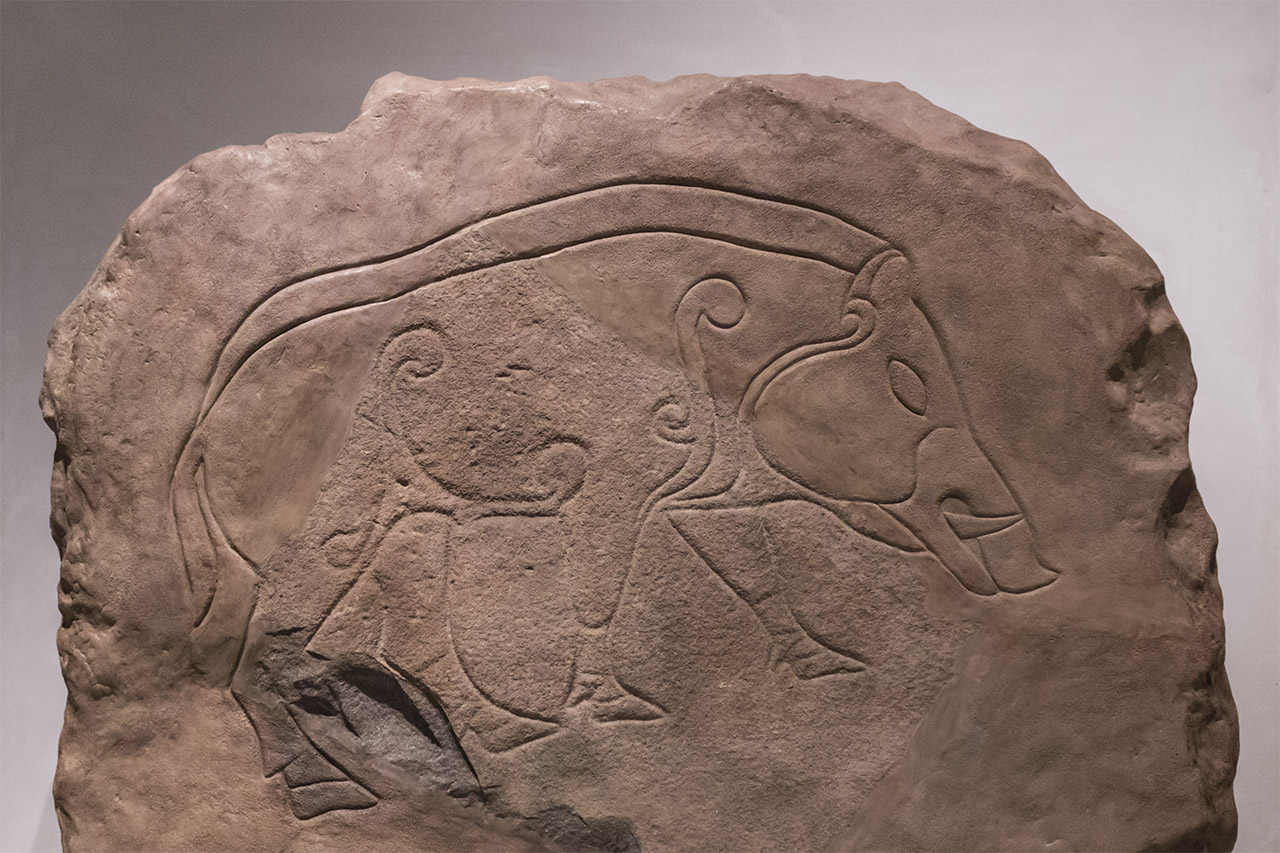

Recently on the Sulawesi Island of Indonesia the following cave painting of a boar was found, believed to be 45,000 years old, making it one of the oldest cave paintings ever found.

But why the boar? What is the connection?

To solve this mystery we need to understand that these areas were ruled by Hindu kingdoms, and the people practiced Hinduism for thousands of years in these regions.

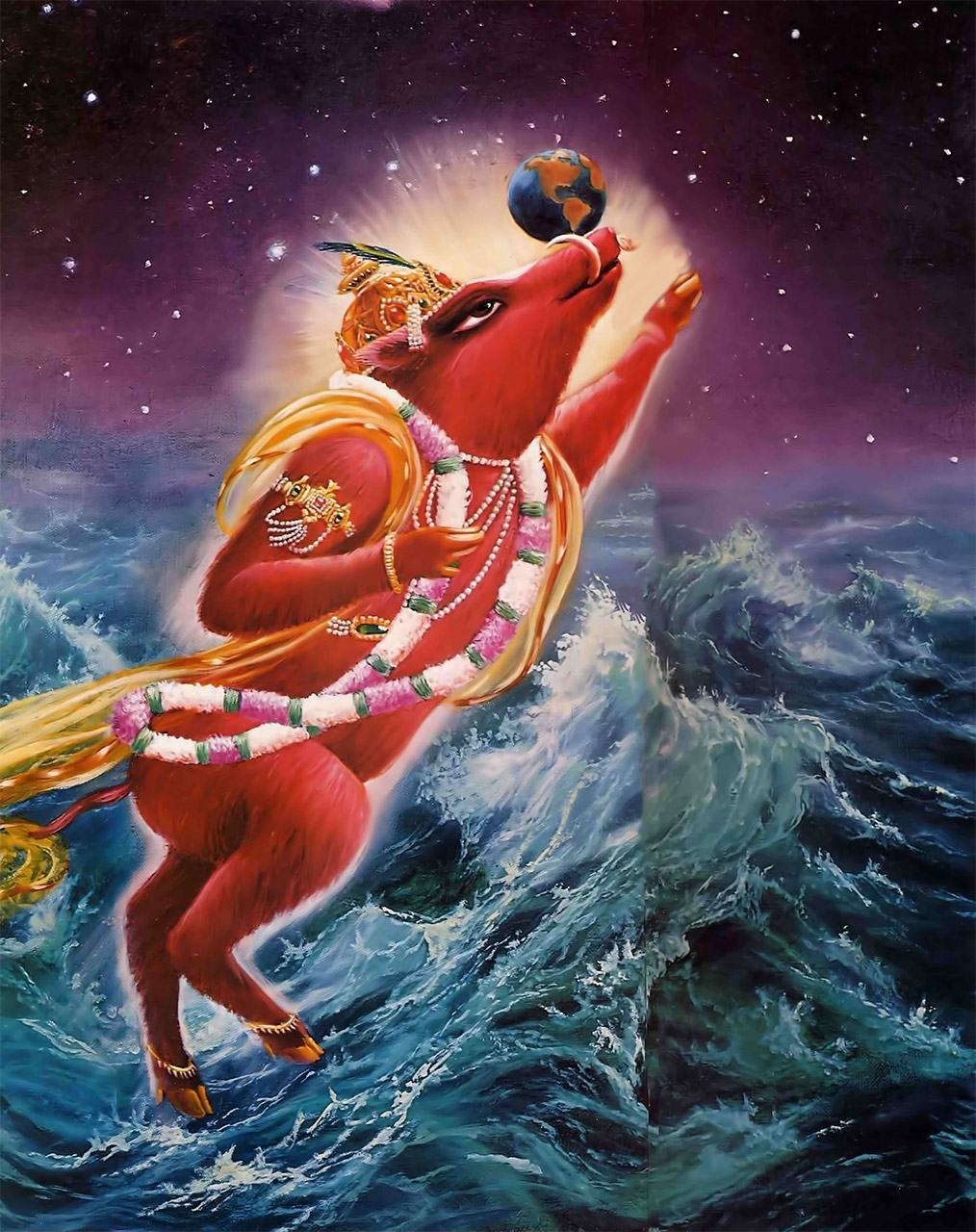

In the Hindu scriptures, this planet is known as ‘vasundharā’. The word ‘vasu’ means “wealth” and “dharā” means “one who holds”. We are told that in Treta Yuga (the second age) the Lord assumes the color red to establish the fire sacrifice (yajna) as the yuga dharma or process for self-realization for that age. The presiding deity for that age is known as Yajna Varaha (the boar).

According to King Prithu (in the Srimad Bhagavatam), whatever is taken from the Earth, whether from the mines, from the surface, or from the atmosphere, must be considered the property of the Supreme Lord and thus must be used as a sacrifice (yajna) to Lord Vishnu.

In the Srimad Bhagavatam we are told that in this second age a great asura (demon) named Hiranyaksha, being inimical to the Lord, strip mined the Earth of all her precious metals and jewels. The Earth became unbalanced and fell into the universal waters of devastation.

The Lord then assumed the incarnation of Varaha (the red boar) to lift the earth out of the waters. The Lord thus saved Bhu Devi (the goddess of the Earth) who is also Lakshmi, the goddess of fortune.

Other references connecting the boar to wealth are to be found:

In the Taittiriya Samhita (6.2.4) we are told that the boar “plunders the wealth of the Asuras”.

In the Panchamukha Hanuman Kavacham we read: “ōṁ namō bhagavatē pañcavadanāya uttaramukhāya ādivarāhāya sakalasampatkarāya svāhā”.

This tells us that the Northern face, which is Adi Varaha (the “original boar”), is called the “giver of all wealth”.

Kuvera, who is a pot-bellied dwarf, is the treasurer of the Devas (demigods), and sits upon a wild boar as his mount (vahana). He holds a money pot holding coins and is the guardian of the Northern direction.

In this simple image of the piggy bank we see echoes of the Vedic past – the clay symbolizes the goddess of the Earth, the coins symbolize the goddess of fortune, and the earthenware shaped as a boar is the presiding deity of sacrifice Yajna Varaha, who is the giver of all wealth.

The first European record we have of the Majapahit Empire comes from an Italian Franciscan friar. In his book “Travels of Friar Odoric of Pordenone” he records visits to Indonesia, including Sumatra, Java, and Borneo, between the years 1318-1330 AD. He returned back to Europe via the Chinese silk road in 1330 AD bringing back this connection for a coinbox shaped as a pig.

In Europe there were still remembrances of the connection between the boar and good fortune. Tacitus tells us of the Aesti tribe of northern Germany who worshipped Freyja (Friday) who is accompanied by her boar Hildisvini (‘Battle Swine’). She is the goddess of love, fertility, and gold. Her name is cognate with Sanskrit ‘priya’ meaning beloved. Her brother is the Norse god Freyr who rides his wild boar called Gullinbursti (‘Golden Mane’). In the Norse tradition the four corners of the sky are held up by the dwarfs Norðri (North), Suðri (South), Austri (East) and Vestri (West).

The Irish too had a great reverence for the boar. In the Gaelic language Ireland was known as Mucinish or the Island of Boars. This is because the boar was the most sacred animal to the Druids since they ate acorns from the sacred oak tree. The word for acorn was picbrēd, literally the food for pigs. The boar would act as nature’s plough and helped with woodland regeneration.

The goddess Brigid was said to possess the King of the Boars as her pet and later Saint Brigid, the daughter of a Druid priest, maintained a perpetually burning fire (yajna) at Kildare (Cill=Church, Dara=Oak Tree). This fire burned from the pre-Christian era until the 16th Century.

In the Old English poem Beowulf we find innumerable references to the symbol of the boar as a kind of talisman in battle. We are told they had helmets with the boar attached, a flag banner with a boar’s head, boars made of gold etc. It was believed the image of the boar provided good fortune and protection against injury.

There was even a German board game called Glückshaus (House of Fortune) which made its way to England. This game was played in the 15th and 16th Centuries by tavern goers and mercenaries and featured a Glücksschwein or ‘good luck pig’. And if you wanted to say someone had good luck you would say “Schwein gehabt” which literally meant “got pig”.

Many Gaulish, Germanic, Greek and other nations would adorn their coins with the image of the boar. Even to this day the boar is a prominent animal in European heraldry. Back in India the boar was used as the royal insignia for the Vijayanagara empire. In fact, this empire issued a standard unit gold coin called the Varaha at 3.4 grams.

During the 19th Century migration from the British Isles and Germany helped to popularize the piggy bank in the United States. In England they had used a clay with a pinkish hue to fashion their piggy banks while the Germans were more elaborate with their porcelain porcines. The popularity of the piggy bank took off in 1913 when a campaign was launched to provide little metal piggy banks for homes and businesses to collect small coin donations towards providing relief to those who suffered from leprosy around the world.

This simple little item, deep in symbolism, has been teaching children the importance of learning thrift for many centuries.

In the Rig and Atharva Vedas Varaha is referred to as sukara (Sanskrit सूकर, sūkara), meaning ‘wild boar’. The literal meaning of this word is ‘the animal that makes the sound soo’.

This word ‘su’ from Sanskrit can be found across the world as ‘sow’ (English), ‘sugga’ (Swedish), ‘sau’ (German), ‘sus’ (Latin), ‘hûs’ (Greek), and ‘hū’ (Avestan/Persian) all meaning pig or boar. So nearly every single language in the world has named the pig based off of the ancient sanskrit name of the animal, but only in Sanskrit can we trace out the reason – su-kara, “the animal that makes the sound soo”.

There is one more echo of this ancient tradition you may not have heard about. Throughout the mid-west and southern United States county fairs have a tradition to call out:

SOOIE…. SOOIE….SOOIE… to call the boars home.

Even college sports teams like the Arkansas Razorbacks, who’s mascot is a red boar, have stadiums filled with people calling out:

“Wooooooo…. Pig…. Soooie…. Go Razorbacks.”

Believe it or not, but these are all modern traces of ancient Vedic tradition. They may seem insignificant, but they reveal the truth that once upon a time the Vedic culture was spread throughout every corner of Earth.

Thus ends the tale of the good luck pig that traveled around the world and came back Om.

Other Articles by Vaishnava Das:

The Samurai: Protectors of the Cow

Sweet Salt – The Story of How India Invented Sugar

India – The Land of Stolen Jewels

The Vedic People of Scandinavia

The Vedic People of Azerbaijan

The Vedic People of Lithuania

India – The Land of Stolen Jewels

The Vedic Origins of the Piggy Bank

Soma – Elixir of the Gods

Manu and the Great Deluge

The Legends of Tulasi In Christianity

The Mysterious Iron Deity made from a Meteor

Ancient Shiva Linga in Ireland

Very enriching

Really well researched and informative article. Generally a pig is associated with sloth and dirt but actually symbolizes so many good things! thanks enjoyed reading the article.

Fascinating article, great details and pictures! I appreciate the effort that went into it.

Really a good research and ample examples with vedic origin put up with pictorial representations delights every reader who craves for knowledge. Highly laudable articles. Thank yu for sharing.

Thanks for enlighting us.

Our roots are deeper and longer than I ever imagined.

Interesting Blissful

Hari Bol!

All humanity has done is consistently worked towards destroying or accepting overwhelming evidence of GOD and work towards being inimical towards HIM expecting (hoping rather) to win over HIM in their own immature ways.

Thank you Prabhu for your invaluable piece of work.

Hare Krishna!

Excelente artículo, me encantó leerlo. Muy enriquecedor, tenía una preconcepción del significado del arquetipo del cerdo. Me dieron una mirada diferente… Muchísimas gracias por compartir sus conocimientos 🙏💖✨

Translator: “Excellent article, I loved reading it. Very enriching, I had a preconception of the meaning of the archetype of the pig. They gave me a different look … Thank you very much for sharing your knowledge.”

Thank you for this knowledge

A good research

Very insightful article and we come to know through the extensive research by this author that Vedic heritage spanned the length and breadth of the cosmos. Thank you very much for this knowledge and we now have a moral responsibility to teach this to the younger generation.

Very very knowledgable

This is really informative and I have used this and cited Mr. Das in an article I am writing about the Wild Boar crisis in Kerala. Thank you.

Since my PhD is about cats in India, writing about cats in Indian classical texts, like Marjara and Shashtidevi vahana will help my research. Just an idea. Thanks again.